The debate surrounding ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has sparked a consumer movement that food and nutrition brands can no longer ignore. Our own MD Stefi Rucci recently wrote in The Grocer that the potential legal challenge over UPFs indicates that trust in food is sinking; now is the right time for food and nutrition companies to consider their communications strategies and address the vacuum of user-friendly, trustworthy information on UPFs[1].

In this blog, we explore whether food companies should be adapting their PR and marketing strategies. Staking a position comes with both opportunities and risks, making it crucial to approach the issue strategically.

Media Coverage Affects Buying Behaviour

An analysis of media mentions of ultra-processed foods highlights a dramatic increase in coverage since the publication of Chris van Tulleken’s non-fiction book Ultra-Processed People in 2023 (released in paperback in 2024). Not only are we hearing more about UPFs, what we are reading and hearing has grown increasingly negative since 2022.

Not surprisingly, negative media attention has accompanied a change in buying behaviour: a recent survey by Say Communications in conjunction with Opinium of 2000 UK adults revealed one in three have decreased their consumption of UPFs in the past year. Many of us are worried about the effects of UPFs on our wellbeing and are anxious about consuming them.

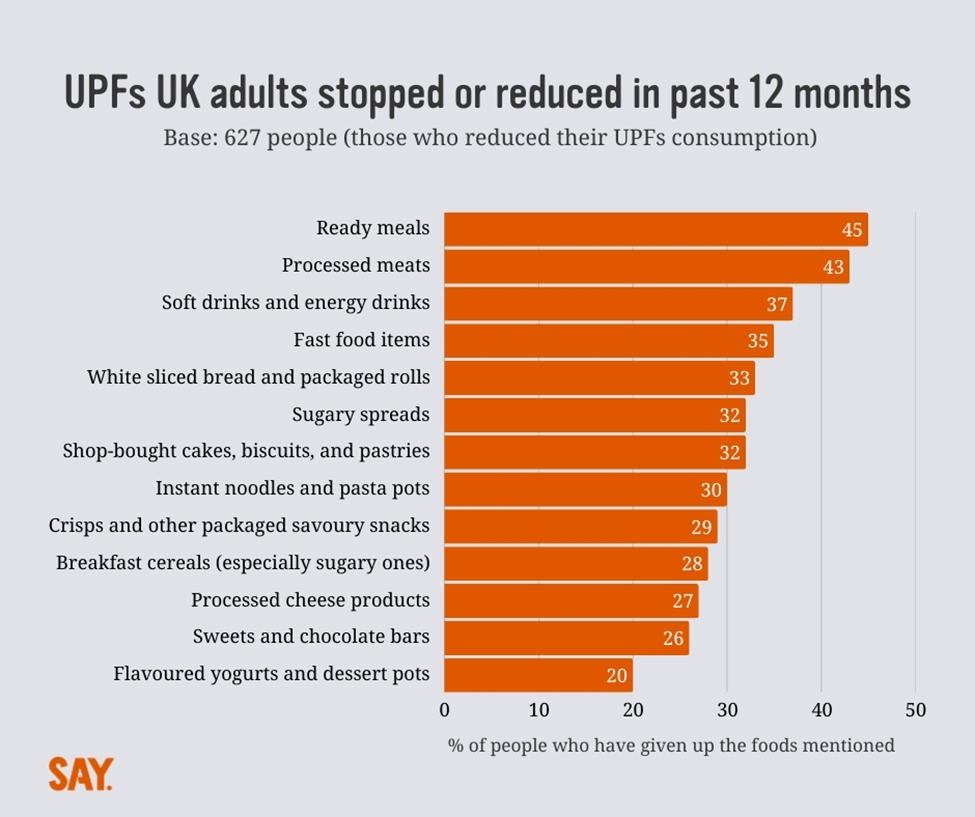

Our survey showed that the top UPFs removed from diets are ready meals and processed meats, closely followed by soft drinks and fast-food items.

When asked how people feel about UPFs, here’s what they said:

- 51% said they’re angry to see the amount of UPFs readily available in the market

- 58% said they’re worried about the effects of UPFs on their wellbeing

- 45% said they’re anxious about consuming UPFs

However, not everyone thinks UPFs are all bad: 30% of people surveyed believe not all UPFs are unhealthy. 24% said they are confused about UPFs.

Confusion over definitions and role of UPFs in policy

“UPF” may be the latest buzz word in the nutrition industry, but should we go as far as considering the extent of food processing when making food policy, as suggested by the Obesity Health Alliance[2]? Are UPFs all bad news, or do we need to better recognise some of the benefits of processing – whether it’s to make food safer, last longer, contain more nutrients, or more convenient?

Part of the challenge is defining what we mean by ultra-processing. Is it the number of ingredients? Is it whether the list of ingredients includes things you wouldn’t find in your kitchen? The most widely accepted definition comes from the NOVA classification scheme, which defines UPFs as industrially manufactured foods that go through multiple processing stages and contain preservatives, flavourings, colourings, and emulsifiers.

With so many opinions and misconceptions, companies have largely stayed away from entering the discussion. Those that have responded have taken two different approaches: Head on (whether alone or as part of a group) or in stealth mode.

Face Head On

Unilever is one of the few examples we could find of a company that has explicitly stated their position on UPFs. “Processed foods play an essential role in sustainable and healthy diets as they increase accessibility, provide affordability, taste, enjoyment and enhance food safety,” states Unilever’s published position statement. The NOVA classification “lacks scientific consensus” and thus shouldn’t be used in policy and regulations, but Unilever says they support further scientific research into the correlation between UPFs and health.

Strength in Numbers: Associations stepping forward on behalf of members

Group pushback is building. The Grocer published an article in 2024 showcasing the trade bodies that are being urged to fight back against the UPF demonisation. The British Sandwich & Food to Go Association, along with the Café Life Association and the Pizza Pasta & Italian Food Association, jointly submitted evidence to the ongoing House of Lords inquiry, defending the use of processing on behalf of their members. Together they represent over 2000 food businesses across the UK.

“The demonisation of large-scale food production is completely wrong as there is no evidence to suggest that the processes themselves are in any way damaging to the health of the nation. Indeed, without these facilities we would struggle to feed the UK’s population. Food prices would be significantly higher which would, in turn, directly affect the health of those less well off; food wastage would rise,” reads the joint statement.

Stealth Mode: Marketing Campaigns Highlight “Less is More”

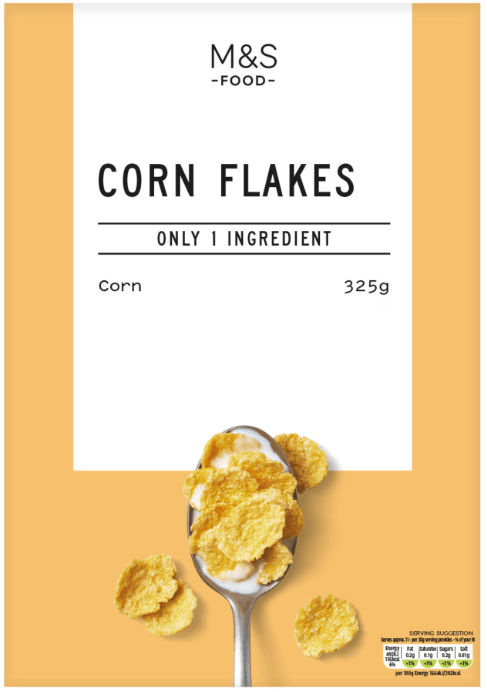

Another marketing strategy becoming increasingly common is to focus on a minimal number of ingredients. Brands taking this approach are tapping into consumers’ demands for “clean” eating without mentioning UPF directly.

A new campaign by M&S has brought ingredient labels to the forefront of their packaging, both figuratively and literally. The cover of the M&S corn flake box proudly displays the ingredients label with only one ingredient: corn. Their ‘multigrain hoops’ and ‘choco hoops’ consist of 5 and 6 ingredients each.

Likewise, Onken recently launched a three-ingredient yogurt for children made from whole milk, fruit and “just a hint” of sugar. The packaging also clearly states it is fortified with vitamin D to support children’s immune systems. Plant-based milk Plenish has claimed to put “wellness at the heart of their products” by keeping their ingredients to a minimum. Jason’s Sourdough is trending on social media for its traditional baking methods and few ingredients. Quaker’s new ‘Deliciously Ugly’ campaign showcases their product as natural as can be, even if it’s not the most visually appealing.

Heinz have taken a related approach by launching a reformulated version of their tomato ketchup with 50% less sugar and salt and highlighting that the product contains less than 10 ingredients. The company claims that this version of their iconic ketchup is “grown not made” and sweetened from a “natural source and with absolutely no artificial colours, flavours, preservatives or thickeners.”

Keep Calm and Carry On

The NOVA UPF classification system, now well-known among the public, can feel like a blunt instrument when used without additional explanation. This may be the right time for food and nutrition companies to consider how they are connected to this cultural shift, rethink their communications plans, and communicate better.

With most companies staying quiet, there is an unmet need for user-friendly, trustworthy information to support consumers who are too often in a state of confusion, or even worse, fear, of the foods they are consuming. Consumers want honesty and transparency from food manufacturers so they can make the best choice for themselves and their families.

Whether companies decide to defend processing, reformulate, repackage, stress their healthy credentials or stay quiet, it’s important to consider what the debate will mean for your brand. There’s no “one size fits all” solution; each company should be prepared for future scrutiny and decide its own unique strategy.

As food and nutrition communications experts, we at SAY Communications can work with you to build your brand’s narrative, develop PR and marketing strategies, and help build engagement and trust with consumers. Get in touch with our team at hello@saycomms.co.uk to learn more.

[1] S Rucci, “A legal challenge over UPFs? Trust in food is sinking”, The Grocer, 15 March 2025.

[2] How Do We Talk About Ultra Processed Food in Policy?, 9 May 2024, https://obesityhealthalliance.org.uk/2024/05/09/upf/

Find out more about how SAY can support your organisation with nutrition and food PR.

Need a helping hand to overcome your communications challenges? Why not contact SAY for a free advice session?